Why Starbucks Failed in Switzerland

A global icon entered a wealthy, coffee-loving market and still stumbled. The reason wasn’t product quality or competition. It was progress mismatch.

A few days ago, I walked past the Starbucks at Stauffacher in Switzerland—and it was closed. For a brand that has dominated coffee culture worldwide, seeing an empty store in a prime location is striking. The problem isn’t the coffee. It isn’t the price. It isn’t even brand awareness. The real issue lies in the (outdated) business model and how it interacts with customer behavior.

Starbucks is one of the most recognizable consumer brands in the world. It scaled across continents, cultures, and income levels. It reshaped coffee consumption, normalised on-the-go rituals, and turned cafés into “third places” long before the concept became mainstream.

So why did Starbucks fail in Switzerland — a wealthy country with high purchasing power, strong urban density, and an established café culture?

The answer is not about price, quality, or competition.

It is about a misread job to be done, flawed assumptions about consumer progress, and a deep misunderstanding of the local social logic behind coffee consumption.

This failure is not a Swiss anomaly.

It is a perfect case study in innovation strategy, business model adaptation, customer discovery, and why global concepts collapse when they clash with local progress patterns.

For more on opportunity management in innovation, this article might be interesting to you:

https://innovationand.org/p/beyond-the-opportunity-landscape?r=gnh4s

The Assumption: Coffee = Coffee

Starbucks entered Switzerland with the belief that coffee consumption follows similar emotional and functional patterns across markets.

In many countries, that assumption holds.

But Switzerland is different.

Swiss coffee culture is:

embedded in daily rituals

tied to local bakeries, cafés, and neighborhood identity

associated with simplicity, familiarity, and routine

value-driven, not volume-driven

less about customization and more about quality and efficiency

Starbucks assumed the job was:

“Give me a personalized, premium coffee experience in a cosy third place.”

But in Switzerland, the job is closer to:

“Let me enjoy a quick, quality coffee as part of my daily rhythm without ceremony or performance.”

This mismatch is everything.

“If you want proof that customers hire progress, not brands, just look at Switzerland: Starbucks struggled to fill seats while fast-growing outlets like tiny ViCAFE created queues around the corner.”

The Real Job Performers: Locals, Not Tourists

Tourists kept Starbucks afloat in Switzerland, but tourists are never a stable base for a scalable retail concept.

The actual job performers — the locals — did not experience sufficient progress switching to Starbucks.

Why?

1. Price-to-progress mismatch

Swiss consumers already pay high prices for coffee, but they also get:

table service

fresh pastries

fast delivery

high-quality beans

Starbucks added cost but did not add progress.

2. Third place vs. everyday place

The “third place” story resonates more in the US, where home and work create stress and separation.

In Switzerland, cafés already are informal third places — without the brand theatre.

3. Customization ≠ progress

Swiss customers do not want 12 variations of milk.

They want efficiency and quality consistency.

Starbucks introduced complexity where Swiss consumers wanted simplicity.

This connects directly to the article on why companies misinterpret opportunity:

https://innovationand.org/p/beyond-the-opportunity-landscape?r=gnh4s

The Social Forces That Blocked Adoption

Starbucks underestimated social signalling — a major force in JTBD.

In some markets, carrying a Starbucks cup signals:

urban identity

busyness

belonging to global consumer culture

aspirational lifestyle

In Switzerland, the signal was different:

unnecessary extravagance

foreign mass brand culture

perceived as overpriced rather than premium

not aligned with local taste codes

not associated with sophistication

In JTBD language:

Starbucks failed the social job, not the functional one.

The Business Model Didn’t Match Swiss Behaviors

A business model is not just pricing plus cost.

It is a reflection of customer behavior, willingness to pay, switching triggers, and local context.

Starbucks’ model relies on:

high foot traffic

high customization margins

premium ambience

high-volume beverage turnover

relatively low food expectation

In Switzerland:

food expectations are high

service expectations are high

local cafés dominate loyalty

foot traffic is steady but not impulsive

customization has low perceived value

Starbucks implemented a model optimized for American and Asian markets, not Swiss urban micro-cultures.

For more on how business models collapse when misaligned with progress:

https://innovationand.org/p/why-startups-really-fail-looking?r=gnh4s

Context Matters More Than Category

One of the core insights of Jobs to Be Done:

Context shapes behavior more than category does.

Starbucks looked at:

GDP

urban density

coffee consumption stats

tourist volume

But the relevant context was behavioral:

people drink coffee quickly

people drink coffee in cafés and on the go

people value quality without performance

people maintain long-term loyalty to neighborhood bakeries

people don’t seek novelty in their daily rituals

Starbucks gave the market something it did not ask for.

It tried to overlay a foreign behavioral script on top of a deeply ingrained local one.

The failure was logical.

Almost inevitable.

Why This Failure Matters for Innovation Strategy

Starbucks’ Swiss story is a powerful reminder:

Market size does not predict adoption

Category leadership does not guarantee transferability

Success elsewhere does not reveal local progress

Customers don’t change behaviors just because a brand enters

Jobs to Be Done must be localized, not globalized

And most importantly:

People don’t hire your solution.

They hire the progress it helps them make in their own context.

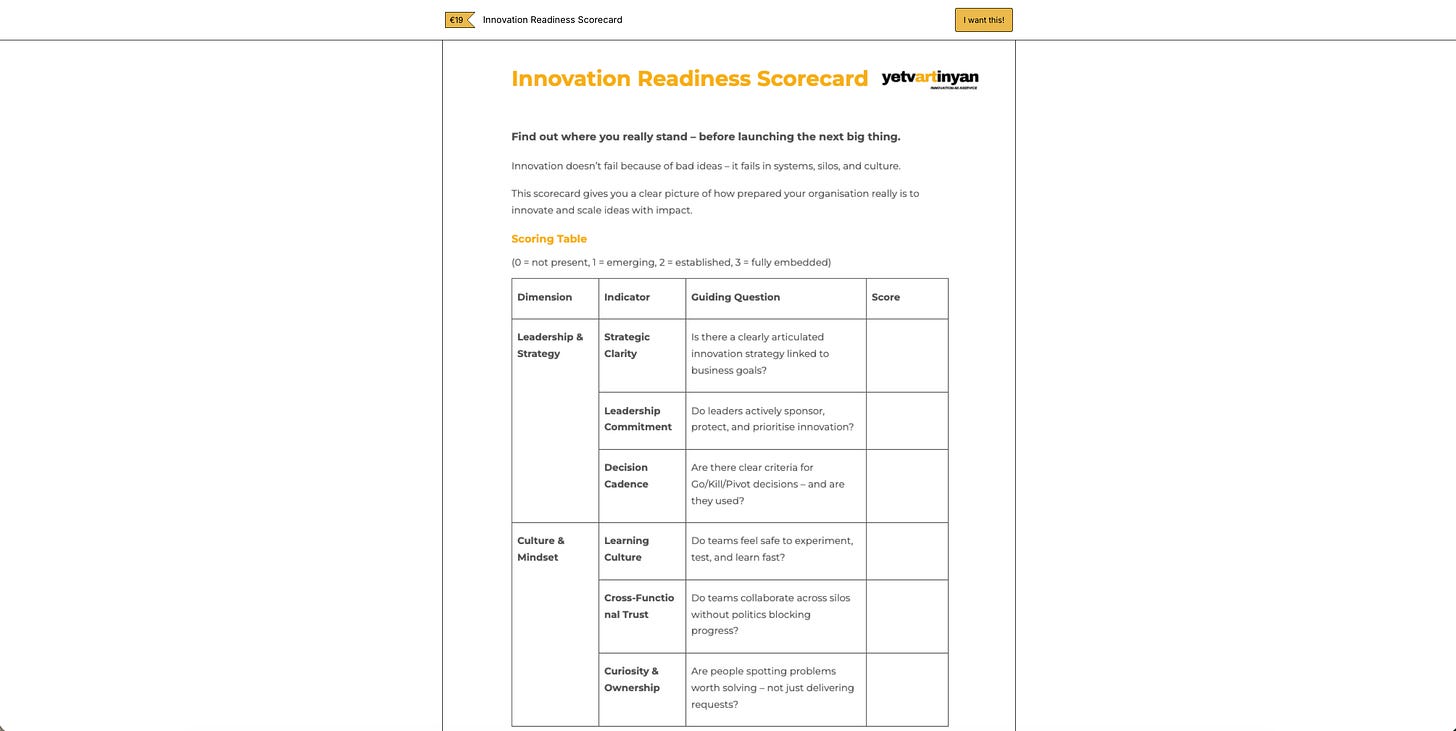

Is you innovation organization ready? Check out my innovation readiness scorecard:

https://innovationand.org/p/corporate-innovation-readiness-is?r=gnh4s

The Swiss Lesson: Progress Before Playbooks

Starbucks failed because it used a global playbook where it needed a local JTBD map.

This lesson applies to:

market entries

corporate innovation

pricing strategy

product positioning

business model adaptation

transformation programs

A playbook is a shortcut.

Progress is the truth.

Companies that look at markets through the progress lens see what others miss.

Companies that copy-paste success stories stumble.

Starbucks stumbled.